|

The Clipper Race isn't a cheap activity. Therefore, it makes sense to do as much as you can to make yourself as useful as possible on the race. To paraphrase John F Kennedy "ask not what your crew can do for you, but what you can do for your crew". Improve your skill set! Making yourself as knowledgable as possible means you can give more to the boat. Giving more to the boat means you get more back. It's that simple. You should read the Clipper Training manual before Level 1, especially if you are a non-sailor. In fact, if you already sail, reading the Clipper manual is probably just as important, because you'll be learning 'the Clipper way'! Ask the office for the PDF. Before Level 1 TrainingThe RYA Syllabus has a logbook in the back which most sailors use for logging their miles and qualifications. If you intend to continue sailing, buy a logbook and get your skipper to sign it at the end of the course - at the debriefing. You need to decide what is useful to you. If you're a non-sailor just buy the Competent Crew book and knots book (or an app). Day Skipper is a bit too advanced. Before L2, reading the easy-to-read books on sail trim would be a great idea. Before Level 2 TrainingLevel 2 is spent largely at sea. After building on level 1 training, you'll be off to experience spending time in a watch system. An ideal opportunity to put into practice sail trim and 'tweaking'. Go play! That's what you are at sea for after all. Team Spirit is just an interesting read. Before Level 3 and 4 TrainingLevel 3 concentrates on spinnaker work and race tactics. By now, learning about the weather is also a good idea. There are books produced by the RYA which cover Northern and Southern hemisphere. Dependent on which leg you are racing, consider buying and reading one. They are well illustrated and easy to read.

Comments

Leg 3 is a biggy ! The Southern Ocean must surely be on every offshore sailor's bucket list. The 'Roaring Forties' below 40 degrees South are renowned for massive low pressure systems and monster waves. Crossing from The Cape of Good Hope to Cape Leeuwin (or thereabouts) means that you have undertaken a big challenge. It gets cold, wild and wonderful. In previous years the race has started in Cape Town and finished in Western Australia (usually Albany or Geraldton).

Pros;

Cons;

Leg 2 is, as the name suggests, still quite early in the race. The round-the-world crew and those that are continuing from leg 1 have some experience and they will know their way around the boat and be much better at sailing her and undertaking 'evolutions' such as reefing and sail changes. Also, leg 1 is over and the race is very much on!

In previous years the race has started in Rio de Janeiro and finished in Cape Town. Pros;

Cons;

(aKnown as one of the 'glory legs' because you get to start the race with all its associated excitement, leg 1 is a long leg (about 5,000 miles). Sometimes split into two races, the leg takes you across the North Atlantic, the Doldrums and equator and delivers you to the southern hemisphere on the South American continent. It is generally warm (sometimes very hot) and the weather is generally less demanding than most of the other legs - although you will see what you think is big weather along the way.. That's until you've finished leg 3!

Pros;

Cons;

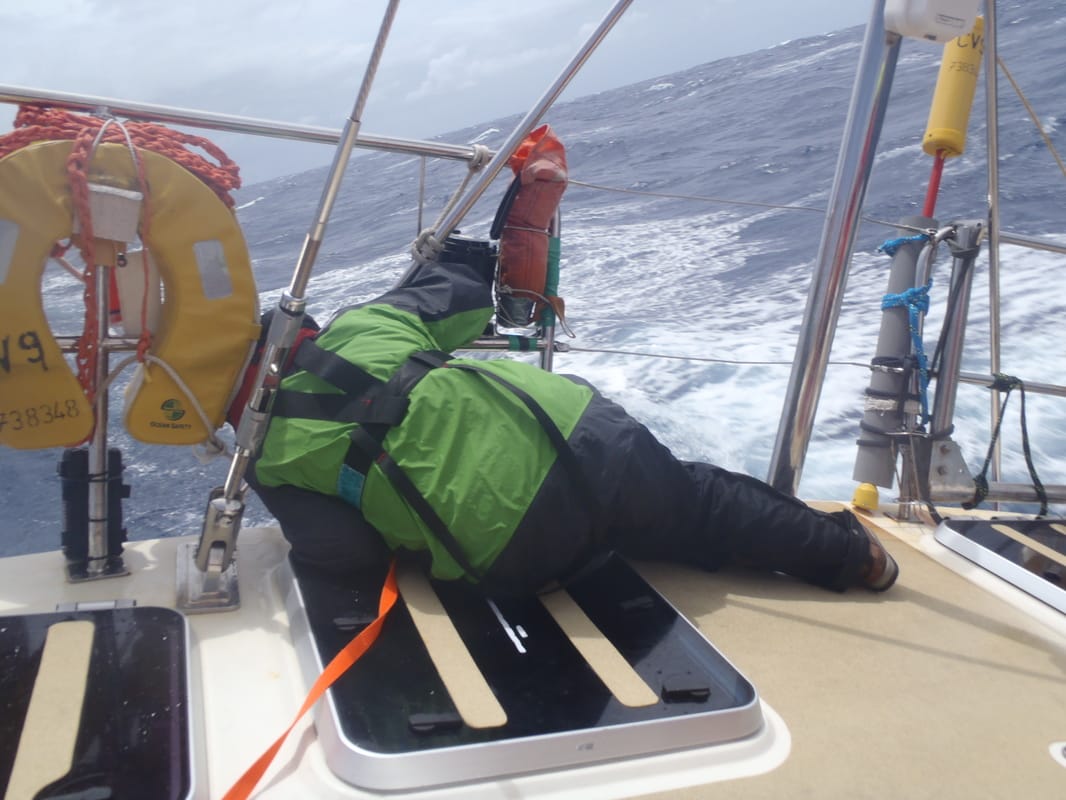

That's my view but if you have a different take on things, please feel free to comment below. If this blog is helpful please consider liking and sharing on Facebook. To subscribe and hear more about the other legs and the race in general, plus crew discounts and flash sales, subscribe. Regular, preventative maintenance of your boat and its systems is critical when undertaking an ocean passage; even more so when you're pushing the boat in race trim. A significant part of your maintenance programme will include your sail wardrobe and standing and running rigging. To check the rig, blocks and halyards, you're going to need to do a mast ascent and this will mean undertaking a risk assessment. Yes, yes, 'Health and safety', but believe me, the first time you leave the rig in an unplanned swing, you'll be a believer! Climbing a rig when underway is different to when sitting alongside a dock.

If you plan on being up there a while, a 70 cm long strop with a carabiner clip on both ends can be useful for attaching yourself more securely to the mast whilst working aloft. Once the climber is ready, check the lines for the climb as follows;

Before you start the ascent, you are going to need something to stop you swinging off the mast and acting like a conker, halfway up. There are a lot of hard, sharp bits of metal up there and you get quite a speed up if you do start swinging. Trust me, I know. I'd recommend using your safety line. Clip it to your lifejacket hard point, then put it around a halyard that goes to the top of the mast (on the same side as the ascent) and clip it back to your jacket. This way, you are not 'connected' to the third halyard but, if you lose connection with the mast your swing will be limited to 2 or 3 metres. It'll still hurt, but you'll be under some control. If you don't have a spare third halyard then rig a downhaul line, attaching it to your harness strong point and running it down to deck, preferably through a block near the mast foot at deck level and back to a winch. This too, will help arrest a swing. On a very large vessel, a downhaul must be used, otherwise, there might come a time where the weight of the halyard in the mast overcomes the weight of the climber and at that point up you go! Not pretty. On the ascent, if you are fit and strong enough to climb, make sure your crew mates know so that they can take up slack as you go. If you're going to be winched, try and stay on the high side and ascend spiderman like, making sure to keep hold of the mast and rigging as you go. If the boat is heeled over, stay on the windward side of the mast and that way you have gravity working on your side. Watch you don't get fingers and heels stuck in the nooks and crannies of the rigging. As you go up, someone needs to be running the deck, making sure winches are being handled properly. Someone should also be 'eyes on' the climber at all times, relaying signals as they ascend. Once there, the halyards should be secured and I'd recommend a clove hitch on top of the winch turns at the end, so as to prevent a line coming off a winch or someone accidentally removing the line. On this point, never leave your winch when there is a crew member on the end of the line! Close the clutches on the halyards if you have them. On descent, first, open the clutches, then remove the clove hitches. Take the primary winch down to the number of turns that will allow you to ease the climber freely, but under control. This will vary dependent on the halyard and winch size but three turns is probably good. The secondary winch needs to be eased faster than the primary (otherwise it'll be a jerky and uncomfortable descent for the climber). You might consider removing turns to 2 turns and let the line run freely as the primary winch controls descent speed. Don't let the halyards run through your hands. Ease them in long, smooth actions, hand to hand - their crotch area will appreciate it. As the climber descends, the person in charge keeps watching the climber at all times and communicating with the deck crew. Once back at deck, make sure all halyards are secured properly to the pin rail, making sure that each halyard run is correct and not tangled around the forestay or rig. Always look up when handling halyards to prevent this eventuality. Despite all of this, it can still go wrong. Just make sure you remain attached to the third halyard or downhaul and a painful swing is the worst you can expect.

Well, those that have done 'a little sailing' tend to have picked up bad habits; habits that they might have been able to get away with on a smaller boat but habits that cannot be tolerated on bigger boats. Boats over 50 ft tend to have quite large loads on running and standing rigging. 70ft boats have huge loads on sheets and halyards and if things break you can get hurt. Therefore, learning where to move around on a boat and where to be safe needs to be taught - and sometimes re-learnt. If you've never sailed before, you get to learn the right way first time. The downside to no sailing experience is that to a large extent you are having to 'cram' an awful lot into 4 weeks of training. In my mind, Clipper Training is the best training of its sort and whilst it must, by necessity, leave gaps in knowledge, it does what it needs to do and covers safety on board, emergency drills, safe line and winch handling and evolutions (sail changes and reefing etc), etc. If you work hard and you're open to learning then, as a 'round the worlder,' you should finish the race a very competent seafarer. You won't be a yachtmaster, but you will have experienced weather and sea states that most sailors will never see and you should be pretty good at helming and trimming sails. If you are an experienced sailor or racer then you might find the first couple of levels somewhat pedestrian but, of course, everyone needs to learn the basics. If you are experienced then ask the skipper and mate if you can get involved with the nav or maintenance tasks or use the time to fill in gaps in your knowledge. Both the skipper and mate are Yachtmasters and cruising instructors as a minimum. Many have done the race before as skipper or they are Yachtmaster Instructor, so they should be able to answer your questions. The Clipper Race runs every other year and training for it is pretty much continuous.

If you haven't sailed before, I suggest you go do some. Level 1 is fairly tame and you'll get a good idea of what's to come, but if you haven't sailed at all, how do you know what you are letting yourself in for? There are plenty of ways to get on the water. I wouldn't recommend an RYA course on the water prior to Level 1 training because, frankly, the skills taught vary so from instructor to instructor that learning the 'Clipper-way' first is probably better. However, if you can get on the water before Level 1 to get a feel for it then great. Dingy sailing is good because whilst its a million miles away in terms of experience, you will quickly get an invaluable 'wind awareness' which will stand you in good stead later. Do some reading also. The boat must come first. That means putting together a full list of things to do and allocating crew to each task. You may have a long list of things to see and do, but there is a real possibility that a lot of them will have to be cancelled if the boat needs work. I say this now because, in my experience of two races, this becomes a real gripe amongst some crew. The fact is, even with the excellent support offered by the small team of shore crew, you will be busy during the stopover and you will be required to give time to the boat in one way or another. Part of the fun of circumnavigating is (or at least it was for me) being part of the circus that travels around the World every other year. Some ports are bigger than others and each one has its own charms. I will promise you one thing. After 3 or 4 weeks racing across an ocean, making landfall is a very pleasant experience! But when you get to the finish it's not all parties and story-swapping. There is work to be done - and sometimes lots of it. Also, if you happen to have had a bad race and finished late, you have less time in which to do this work.

This will include PR visits, radio and sometimes TV interviews, skipper meetings, corporate sailing days and the like. During my time as skipper I could never find enough time in the stopover - it was manic. On top of maintenance there are the corporate sails. These are days where the sponsors get to entertain clients on day sails. As part of your crew contract, you may well be required to participate in these days. I always used to enjoy these days, but they are full on and generally you have to write off at least half a day for this - assuming you swap out at lunchtime. Of course, as long as you get in on schedule there is no reason why you can't have 3 or maybe 4 days to yourself. The better you do in the race, the more time you are likely to have! So there's a real incentive to be first boat in.

Keeping warm at sea is just a matter of preparation and attention to detail. Of course, on some of the warmer legs, such as leg 1, leg 7 and much of leg 5, keeping warm on board is not a problem. In fact, dealing with 40+ degree temperatures and high levels of humidity below deck is the biggest challenge. If you want to read more on these warmer legs and how to keep cool, click here. In my experience, staying warm requires that you look after yourself by eating well, staying active and staying as dry as possible and as well insulated as possible. Staying active on the race is rarely a big problem but there is an art to choosing the correct clothing for the conditions. On a very cold night at sea, when it's wet and rough, with water over the deck (and the crew), staying dry and warm without overheating when busy changing sails, can be tricky. The start of a watch might have you thinking you are under-dressed, and feeling the bitter cold and yet 30 minutes later you might be sweating profusely having just dragged the yankee 1 down the deck, battling against sea state and gale force winds. Understanding the best way to layer is therefore important. For a cold ocean, you should be dressed as follows;

This is my suggested packing list for Level 1 Training.

Other useful stuff to consider:

Level 1 starts alongside. I guess it'd be hard to start anywhere else! However, expect to be alongside until lunchtime on the first day. There is a lot to learn before you go sailing. At the time of writing, Level 1 Course start at about 1700hrs on a Thursday and you slip lines about lunchtime (ish) the following day. This may change over time so always check with Clipper.

Clipper will have told you when to rock up, which boat you're on and it's likely you'll know who your training team will be. Each yacht has a skipper and a mate and it's likely they will be on board for several hours before your joining time. If you are early, it's best to let the office know you are there and use the opportunity to do any paperwork. Don't bother the skipper and mate as they'll be busy doing rig checks and paperwork; so try to keep out of the way until your designated joining time. In any event, you probably won't be able to get onto the dock as you won't have a security tag. These are issued by Clipper after you formally join. You can always fill time getting a coffee. Go to Hardys or The Boathouse and practice your knots over a coffee. Or alternatively try out the cakes at The Pumphouse located about ten minutes walk away. Or there's the Castle Pub at the marina entrance, but probably best not to meet your training skipper smelling of booze. Alternatively, Clipper want you to try on your race-sponsored gear (where provided), although this is normally done later in the training process. Perhaps have a browse of kit in the office ? If you want to go for a wander, the office may allow you to leave your bag with them if you smile sweetly (assuming they have room). It does get pretty manic in the run up to the race. If the delights of Portsmouth appeal, take a foot passenger ferry over to Gunwharf Quay, a large and modern waterside shopping and leisure complex. The ferries run regularly about every 15 minutes and the terminal is close to the Gunwharf, which is 5 minutes walk from the Portsmouth side of the ferry - ask for directions when you get there. Basically, walk to the taxi rank and turn right, following the main road for about 100 metres. The Course Content Level 1 is your introduction to Clipper and, for many, it's also an introduction to sailing. It's often stated that something like 40% of all Clipper Crews have never sailed before they start training. That's quite a startling statistic. Of course, many have sailed for years, although few have sailed boats over 60ft. There is a big difference between a 36ft family yacht and a 68 - 70ft ocean-going race boat and so, in that respect, all training crew are more than literally 'in the same boat'. Clipper will say it best but, in basic terms, this writer would sum up Level 1 as being an introduction to the boats and how they work, basic sailing principles and safe seamanship. At the end of Level 1 you should be a relatively safe and reasonably competent crew member on a Clipper boat. In three words, Level 1 is primarily about safety, safety and... safety. It's also quite a shock to the system if you've spent a couple of decades driving a desk for a living and sleeping in your own private, centrally heated bedroom! Day 1 starts on arrival at 1700 hrs and after a brief 'get-to-know-you' session, you'll be straight into safety briefs below deck. School night nerves? What to expect. Arrival always reminds me of the first day at school. Lots of crew members all nervous and excited, perhaps a little apprehensive. It's quite sweet really : ) A new environment with lots of strange new things and dozens of new terms to learn and understand. It can be daunting for the complete novice, but don't worry. The guys and girls in the office know exactly what they're doing and they are great at putting your minds at rest. Many are keen sailors or they've done the race themselves, so you are in good hands. The skippers and mates are, to a greater or lesser extent, fairly well house trained, civilised types and rarely bite unless the teas and coffees stop coming to deck! Remember, they do this every day of the week. You simply cannot ask a stupid question. At least, not one that hasn't been asked many times before. So, deep breath, smiley face... and begin. We'll assume that you've made it to the training office on time with all your kit for the week. You also have your passport safe and Clipper have done all the formalities. You'll have signed all the next of kin forms, have insurance and you're ready to go. Remember, if you are training between October and May in the UK it is likely to be very cold at night on board and during the day at sea, so pack sufficient kit. On the race you will be limited to between 20 - 25 Kg of kit (usually plus foulies and sleeping bag), dependent on your skipper, so try and start being ruthlessly efficient when packing for training. After all, it's only a week. Suggested packing list for Level 1. CLICK HERE You will usually be met at the Training office by your skipper. Hopefully you are carrying no more kit than a rucksack or sailing bag and a sleeping bag. If you have more then you've probably overpacked. Clipper provide foul weather kit for training so you just need to bring stuff to keep you warm. The first evening is spent getting to know the skipper and mate and the rest of the crew. You'll all be walked through the boat and talked through its systems in quite a bit of detail. Everything from how to safely secure your bunk to where to find the fuel cut-off valves and life rafts. All will be addressed. Then, you'll go through the course and this is where you get an idea of how the skipper has planned the week. He or she may decide to allocate crew to watches (your team within a team for the week) and within each watch there are various crew functions. Every skipper has a preference. You'll also get a bunk allocated and you can start to stow kit either then, or later, dependent on the skipper's preference. Top Tip: Keep your kit in your bag (preferably decanted into one or two dry bags) to keep it dry. The smaller bags are good for 'decanting' stuff into for organizational purposes! The 'cave lockers' on a 68 (the old fleet, usually used for Level 1 training) can get quite wet and unprotected kit will be soaking in no time. On CV6 Geraldton on the Pacific leg (a very wet leg) I was bailing bucket loads of water out of my cave locker every day (can you hear violins?). My kit was floating in sealed dry bags (yup, definitely violins). Training isn't that bad because you don't get as much water over the deck, but the lockers still get wet. You might also want to invest in a waterproof phone case for the same reason. Dependent on crew numbers you will each have a specific responsibility, as well as sailing. This might be 'mother' duties (cooking for the entire crew and washing up after) or engineer. Navigator or cleaner - or deckhand. All crew are expected to take responsibility early on. You will be shown what to do and you are encouraged to ask if unsure, but the responsibility for your job is yours. Without delegated tasks and responsibilities it will quickly become apparent that a large yacht will grind to a halt, fast. Taking the delegation of responsibility seriously is important. Don't worry if you know nothing about rudimentary checks on diesel engines, the basics will be taught through the week. The same with navigation and log keeping. If you can't make pasta or boil an egg it might be worth getting some tips on basic cookery though! The delivery of warm, edible food on time for 12 people can be quite daunting for the novice, especially when working in a small galley at sea. The first night is a good time to let the skipper know of any physical or health issues (although he should already have been told - which means you need to have told the office) and if you are allergic to anything or have dietary requirements this should have been allowed for in the food shop (victualling). Don't be embarrassed to check, just in case! What's a 'watch system'? Basically, it's shifts. You work for say 4 hours, then rest for 4 hours and so on. During training you might be split into two watches, usually between 4 and 5 on each watch. You won't be in a proper watch system until your first night at sea, possibly much later in the training (Level 2), but as the course progresses you will probably be split into watches to do sail changes, reefs, etc. When day sailing you may be split into watches for evolutions, but you won't usually go off watch. Each watch member is paired with their opposite number on the other watch. Then when it's your time to be 'mother' or 'engineer' you share the duties with your crew mate. It means there is always someone on watch to make the tea or fix the heads! On the race, living in a watch system becomes normal after about 3 days and whilst you probably only sleep for about 2 - 3 hours at a time, it's amazing how quickly you get used to it. That said, on L2 Training you will work all day on the first day and then as and when you go offshore, you'll go into a watch system (usually after dinner). Because you haven't had much of a chance to 'claim back' the sleep you lose on the first night, you will be tired at the end of the 'sea phase' and that assumes you have been able to sleep at all. A word of warning - when in a watch system, it's critical that you turn up on deck and announce yourself (so they know you are on deck at night) at least 10 minutes before your watch starts. This means getting up in time to wash, dress (and possibly eat too) before you go on deck. Get it right. Turning up late to your watch is probably one of the biggest sins you can commit on a sailing vessel. Tired, cold people rarely have much patience for such inconsiderate behaviour... You have been warned : ) Top Tip: 'Mothers' remember you need to feed the watches on time to avoid late watch changes! Food & Diet Food on board is usually simple but warm, nutritious and provides sufficient calories for the day. On the race, a cold leg will usually have the average male crew burning 5,000 calories per day. Training is much less demanding, but you will want to eat! Most skippers provide victualling for a meal plan including for breakfast, a simple lunch of soup / sandwiches, baguettes or similar and a warm evening meal. There are usually plenty of snacks, biscuits and fruit. If you have special dietary needs (and especially allergies) tell Clipper - well before you arrive! There are no convenience stores at sea. Top Tip: Bringing a couple of bars of chocolate with you for a midnight-watch treat does wonders for morale on a cold, dark, rainy night and makes you, unsurprisingly, very popular amongst your crew mates. Skippers usually split jobs into a daily rota with two people (one from each watch) working together to complete the various jobs. This is managed so that the day is, except for lunch, largely left free for sail training, although mothers and navigators have to juggle their responsibilities around their own tasks. Of course, whilst you are expected to do your job, the training team don't expect you to take charge of the yacht's actual navigation. They will always know where they are and where they are going! What to pack and what to buy for training? Keep your money in your bank account for as long as possible. Certainly, once you've had a chance to decide what might suit you, come to us and we'll be happy to sell it to you! If we don't sell it check out our list of retailers that are worth speaking to (some even give Fierce Turtle members a discount). But in the first instance, simply splashing cash is premature. Make sure you download our recommended packing list. Ask fellow crew about their kit too. But remember what works on Leg 7 won't necessarily be sufficient for Leg 3. For example, I have no doubt that anyone doing a cold leg will want a good, marine sleeping bag. For the race, you will all need good mid layers and proper, 'wicking' base layers and lots of other stuff to, but for training as long as you have a warm, quick drying fleece and a few warm, thermal beanies (woolie hats) and buffs (tubular fleece neck scarves/gaskets) and gloves, you will be fine. You will also need good ocean going sailing boots if you are doing legs 2, 3, 4, 6 or 8 (and the last week of Leg 5) but unless you are absolutely sure you are doing the race, I'd recommend you hold fire on spending too much too soon. If you have decided to splash cash now, check out our kit reviews here. In response to demand, we also offer crew in training Le Chameau Neptune boots on hire for just £49! Click here for details. If you are training in the UK between January and March I suggest you consider hiring a marine sleeping bag. These are fleece lined, warm, waterproof and very very comfortable. Click here for details of our offers. When you do buy, buy the very best you can afford. Subscribe with us for flash sales and crew discounts! For a week's inshore sailing, as long as you have two pairs of grippy shoes with non-marking soles (in case one pair gets wet) and a pair of boots (cheap sailing wellies will suffice for Level 1 - with decent grippy soles) but the hire option is worth considering.. At the time of writing, Clipper provide foul weather salopettes and jackets, so it's just the other stuff you need to bring. If you are the proud owner of a smart phone it's worth considering a waterproof cover to keep it safe from the wet environment. Level 1 Course - Day 2 onwards Most of the morning is taken up by an introduction to the boat's deck, safety procedures, communications equipment, line handling, rigging the boat for sea, taking down weather forecasts, passage planning and general preparation. The principles of the recovery procedures in the event of a man overboard, the use of flares and other equipment and basic VHF communications will also be addressed. Boats are usually away from the dock after lunch and the rest of the day is based around hoisting the sails, introducing crew to the principles of sailing, 'the tack' and 'the gybe' and possibly a little time looking at points of sail. During the day crew will be handling sails and lines and some, probably not all, will have a chance at helming the boat and managing it, dependent on their roles and responsibilities for the day. At the end of the first day, the training yacht will usually return to Gosport in the early evening (say 1830hrs) and after packing away the boat and sails all will return below for a well-earned evening meal, cooked by the designated mothers. After supper there is usually a short crew debrief and if people are still awake there may be a short lecture on the skipper's chosen topic. This is usually delivered by the training skipper or mate and may involve a 'whiteboard' session and some discussion. The day normally ends after mothers have washed up and it's not unusual for crew to get away to the local pub for a 'swift shandy' just before last orders. Then its a shower for the more fastidious, before collapsing into your bunk, tired and cheeks burning from a day on the water. Level 1 is primarily run 'inshore' with 'passages' reserved for later in the training process. Each day builds on your new-found knowledge. The training team will plan the delivery of the course around the prevailing weather conditions and crew strengths. Different points of sail, reefing procedures, sail changes and emergency drills and man overboard recovery are all covered. It's very unlikely that you will see a spinnaker (the biggest downwind sail on the boat) on Level 1 and the boat is unlikely to venture far from the Solent and its approaches. After all, the skipper and mate need to be sure that the crew are at a sufficient level of competence before they leave the comparative shelter afforded by sailing inshore. The last day will find you returning to the local area and upon return to Gosport you will be introduced to the delights of 'the deep clean'! A deep clean is, as the name suggests, a comprehensive 'strip-down' of the boat and a thorough scrub of everything including 'the heads' (toilets), the 'galley' (kitchen), lazarette (stores/garage) and bilges (no explanation needed?). This is a critical but less exciting part of the course and it is something you will do many times during your Clipper Career, although it's somewhat less exciting than the sailing. It involves some mucky work and whilst it might be tempting to slack a bit, skiving off the 3 - 5 hours it might take to do a proper deep clean (dependent on crew motivation) will quickly make you unpopular amongst your peers. It also makes for a slower clean, so try and get stuck in and resist the temptation to 'just take your bags to the car'. No-one is finished until the job is finished; very much the spirit of the race itself. Of course, I know you wouldn't do such a thing dear reader, but some weaker characters might be tempted. On the same subject, when travelling to and from the course, make sure you allow enough time for participation in the deep clean. During the clean the skipper will usually use the time to start debriefing crew on their week and finishing their evaluations. Skippers make a recommendation on whether individuals are sufficiently competent to progress to Level 2 and in most cases the training is comprehensive enough, and the enthusiasm of the crew is strong enough, for most to pass. Sometimes a skipper may suggest more time on the water before Level 2. The office can normally arrange this for you if you speak to them. In most cases a plan for the remainder of your training will be discussed during the debrief and this is also a chance to share your feedback on the week and share your concerns or questions. "Remember, there's always one crew member on any boat that has the potential to be an irritating prat. If your boat doesn't have one, just allow for the possibility it might be you.."! The debrief is where you get an insight into your sailing capabilities from the mouth of a professional and sometimes the experienced boat owner is surprised at just what they have learnt during the week. Even the most experienced of us learns every day we're on the water - if we let ourselves! It's also used as a sounding board for crew and its an opportunity for skippers to raise any non-sailing issues with crew. If your skipper starts talking about 'tolerance of others' and how 'some people are, perhaps, er too strident in their views..' and suchlike, he or she may be trying to tell you to 'wind your bloody neck in a bit!'. One of the hardest parts of racing around the World is crew dynamics and whilst our individual idiosyncrasies and character traits might be easily forgiven ashore, on board a 70ft fibreglass tube for weeks at a time, they quickly become very irritating. Part of a skipper's job is to try and address these issues with crew members early on. It's not easy and they don't do it because they enjoy it. But it is important to listen if you do hear a little criticism in the debrief. None of us are perfect. On the last night it's normal for the crew to get together for a meal ashore. Every meal during your week will have been on the boat, so a little civilisation is usually welcomed by now! It's a chance to have a chat about your new adventure, laugh about your cock-ups and build on new friendships over a couple of glasses of wine. Some crews take the opportunity to reward their training team with a meal, some don't. It's entirely a personal preference. By the end of the week you will know how to sail! OK, you may be no expert, but you'll be effective crew and able to rig the boat, de-rig it, undertake basic checks, know various skills and drills and generally be a useful member of crew. Then you can look forward to Levels 2, 3 and 4 (aka BIG school)! In any event, you should be confident of one thing - you will LOVE IT! Promise. Alcohol On Board Remember, alcohol onboard is very strictly forbidden. Drinking alcohol is, in general, not encouraged during the course - certainly not when on the water! After the crew meal on the last night it is tempting to let your hair down. We are (most of us) grown ups, but beware, being 'drunk' when coming back to the boat on the last night won't be tolerated by the skipper, or Clipper, and if you do over-indulge don't be surprised if the skipper invites you to end your course by sleeping on a park bench in Gosport! It's his livelihood at stake and you are his responsibility on board, so its best to respect that reality. If you are late back your skipper won't thank you if he's had to wait up until you are safely back on board. Remember, the marina is tidal and cold. Falling in is a serious matter and potentially fatal. The Last Day The last day starts with breakfast and whilst the skipper starts debriefs the crew will start the deep clean under the instruction of the mate. It's usual for all crew to be free to leave by no later than 1400 - 1500 hrs on the last day of a course (usually a Thursday for Level 1). Check with the training office if you aren't sure of timings as these may vary. Smoking on board As a non-smoker, this has never been something I have needed to consider. Certainly smokers are becoming less and less prevalent on the boats. Once upon a time it seemed like every sailor smoked; less so now. That said, there are usually some fairly basic rules on board any boat and they are likely to be the same rules that your skipper will lay down. In any event, and subject to each skipper's rules, if you are a smoker it's unlikely you'll go far wrong if you do what you'd normally do;

Showers & General 'Landlubber Prettyfying' On Level 1 most nights will be spent alongside, meaning showers and toilet facilities are available on shore. Luxury! I have found a large travel towel is useful as it dries better and doesn't smell when damp. Ten damp towels in the accommodation area (The Ghetto) make for an interesting aroma after Day 4. Hopefully this has given you a pretty good outline of what to expect from Level 1. Please comment below if you have any questions. Also, check out our blogs and FAQs for other information. Sail safe ! Parking & Travel Clipper have a dedicated car park at Gosport Marina. It has a gate and is therefore relatively secure, although open to pedestrians. You can reach Gosport by car or train (via Portsmouth & Southsea Rail Station and the short pedestrian ferry ride to Gosport). The marina is 3 minute's walk from the ferry terminal, next to the Castle Pub. Those of you that have read 'Tales of the Riverbank', might believe that there's "nothing but nothing so absolutely wonderful as messing about in boats", but I'm pretty sure Badger and Ratty hadn't been on the weather rail all night, downwind of a projectile-vomiting Toad. 'Mal de mer' as the French would say, is basically motion sickness; the disconnect between what your eyes are seeing and what your balance receptors are telling your brain. It causes the body to react and it makes you feel nauseous - and sometimes vomit; sometimes spectacularly. In itself this is nothing but unpleasant, although in severe and prolonged cases it can cause dehydration and therefore result in further complications. It is therefore imperative that you keep an eye on a sufferer and encourage them (without nagging) to keep sipping water even if they are feeling very ill. Remember too, if you are taking medication, including the contraceptive pill, you are in danger of losing its beneficial effects after a bout of vomiting - even once home. If you suffer in cars or on flights, it is more likely that you will need to medicate when at sea in rough weather. Common sense would suggest that if you already know that you suffer, be prepared. The key is to medicate early (12 hours before you sail) if the remedies are to have a chance to work. They do say that there are only two types of people in this world; those that suffer from sea sickness and those that have yet to suffer. Most people are not normally sea sick, although many worry themselves unnecessarily about it. I'm one of the lucky ones. I did feel sea sick when I first started to sail 25 years ago but almost never was, except for one night in a F10 storm off the Moroccan Coast. Nowadays I don't even think about it - although I am very aware that we can all get it if a bit under the weather, so I am not saying it won't hit me again! Anyway, Lord Nelson was sick every time he went to sea and he was quite a decent sailor by all accounts. The good news is that sea sickness will pass. On the race a severe sufferer might be ill for 2 - 3 days. As the weather abates they recover. The more hydrated you stay the faster you get better. Most are only ill when it's pretty rough and even then, only for the first 24 - 36 hours of a trip. Unfortunately most early offshore phases in Training are 24 - 48 hours in duration, so if you are one of the unfortunates you might not see the other side of the sea sickness coin before you are back alongside. Don't worry - trust me - it will stop, eventually! In any event, like so many things at sea, look after yourself and look after your mate. Be considerate of those suffering - you might be next! And if you suffer, there are always drugs to help... The bad news is that there is no absolutely guaranteed preventative measure available in capsule form. You will need to try several if you suffer and work out what works for you. What makes you sick? A trigger with newbies is extended periods of time at the chart table - or in the galley, so try and avoid that if you start feeling ill and if you do feel poorly when cooking, take a few minutes to get some fresh air and check out the horizon - this really does help a lot. The smell of diesel or a flushed heads (toilet) can set you off too. You can see why being below is a factor for some. If you allow yourself to get too cold or too warm it can strike the more susceptible. It also prays on the hungover and those feeling 'under the weather'. Apparently, women having their period are more likely to suffer, although I'm afraid I'm no expert in that department and will steer clear of advice there. The classic for Clipper Racers in Training is after dinner on their first night at sea on L2. Eating too many stodgy carbs, going to bed on a full stomach and not getting horizontal fast enough when coming from watch (or changing below to get on watch) can bring it on in the most susceptible. The trick is to get to bed fast when going off watch and get to deck fast (dressed and kitted of course) when coming on watch. Fresh air and watching the horizon helps. Don't get too hot or too cold and sip water and nibble food regularly and you'll be fine. What are the Symptoms? Having sailed for 25 years or more, my general experience of the sea sick is that sufferers normally go quiet for a while first, then pale and sometimes they become cold and clammy. A friend of mine once went an unbelievable green and then deep deep purple. He looked rather like he'd been in a ring with Mike Tyson in a bad mood. It was a sight to behold and, in an uncharitable way, even quite amusing - for me at least. Needless to say, he was a very very old friend. I'm much nicer with training crew..ahem. Sufferers become lethargic and sometimes unsteady on their feet. They can also feel bloated and queasy. Sounds fun so far, right? Thankfully sea sickness isn't life threatening although they do say that the stages of sea sickness start with the sufferer fearing he's so ill he's actually going to die and then, after several hours, comes the awful realisation that in fact, he might not. Don't confuse sea sickness with hypothermia, a much more serious condition and, of course, being sick at sea might be a symptom of something else, so treat a sufferer like any other casualty once they become overcome by the symptoms and unable to function properly under their own steam. Many will never feel anything but just a bit queasy. However, especially if it is rough or you are spending extended times below decks, perhaps doing chart work or cooking, you might become nauseous and vomit. If you start, it's likely that you will soon feel unsteady on your feet and lose strength quite quickly once you are fully gripped by it, especially if you are not eating and drinking. But you can come back from it and some are much better after a quick 'tactical chunder'. It's up to you. What can I do if I get it? Most only ever feel 'a bit nauseous' but if it is rough you might actually have need to call over the side for 'Uncle Ralph' once or twice. Again, this is very personal to the sufferer, but most feel better right after. Some 'puke and play', carrying on as normal, some collapse in a heap of misery. Whilst there is some element of strength of character at play here (and adrenaline plays its part too), I really believe that some people just suffer more. It's not always something you can just power through. I have seen a World Class pro 'Cage Fighter' that knows about physical discomfort and managing it just crumble because of sea sickness. He later admitted he'd thought he could just power through, and he did try, but eventually it wore him down. He was the first to admit he had to find a way to manage it - and he did. Try and be brave if you are unfortunate enough to suffer. But if you try your best and have to stop, that's fine. After all, we want you on deck learning, not in your bunk being sick, so try and manage your body early and look after yourself. To anyone that sails, a crew member with sea sickness is no big deal. Throwing up in front of strangers isn't most people's idea of a fun day out but please don't be embarrassed. We've seen it all before. Take it from a man that has been puked on by many. Of course, I'd rather you didn't add to the tally, so please try and control your trajectory. Don't be embarrassed but do try and be considerate of others. If you get sick bad it can be very debilitating. That does not mean you can abdicate all responsibility for hygiene and social decorum, no matter how ill you might feel, try to plan where you puke! I don't enjoy being puked on any more than the next man. If on deck - clip on (of course) and try not to vomit into the wind - it is never a good idea and you'll only try it once. Helming is a good way to get rid of sea sickness. It gives you something to think about and it connects you with the motion of the boat. If all else fails, ask to go below and get horizontal in your bunk. Get warm and comfy and you should start to feel better. Take a bottle of water and some paper towel and a bucket just in case! If below and using a bucket, make sure it is passed to deck to be disposed of to avoid an unpleasant aroma gathering below. Top tip: Best warn the deck what's in the bucket! Most skippers like sufferers to be near the wheel somewhere so they can keep an eye on them - or lying down flat, securely in their bunk, with a bucket, a bottle of water and a warm sleeping bag. Hopefully some kind person will come and check on you every now and again. Try and stay hydrated and warm and don't be tempted to stay on deck on your off watch! You must go below or you'll become cold and dehydrated. Then your problems really start! There are a variety of pills and patches and wristbands available to the susceptible. Patches are quite good but very strong and all have side effects. Check restrictions on use. Ginger and flat cola are considered to be good for the symptoms. Some people use sea bands and some use tablets which you can get from any pharmacy. Whatever pills you take, take them at least 12 hours before you start sailing. If you start taking them late they'll have no time to work. Obviously, if you start vomitting, the tablets will stop working. That's when patches seem a good idea. Double vision, dry mouth and drowsiness are all symptoms of the remedies, so read the box carfeully. Remember, most people are not sea sick, especially in normal conditions. The most reliable way to avoid sea sickness is to stand under an oak tree. However, next best you can try wrist pressure bands, motion sickness tablets or patches. Ginger is said to help and flat coke too. Patches are good because you can't throw them up - worth considering. If you take pills, take them at least 12 hours before you sail, so the night you arrive on the boat before on a training course. If you wait until you feel ill, it's almost certainly too late. The patches are sold under various brands but I think Dramamine is the main brand. It is strong and does have side effects. As with ALL medication, read the labels before taking and if unsure, consult your doctor. |

Mark Burkes is a former Clipper Race Skipper, a round the world crew member, Clipper Training Skipper & jobbing RYA Yachtmaster Instructor. He has over 250,000 miles logged.

Mark also writes professionally both online and offline and has written for Yachting World. ADVICE BY TOPIC

All

Fierce Turtle is not linked to nor is it in any way accredited by the splendid folk at Clipper Ventures. All opinion is my own.

Archives

July 2023

This blog is entirely free. However, if you'd like to make a small contribution towards web hosting costs it'd be very much appreciated.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

fierceturtle.co.uk |

PRIVACY & GDPR POLICIES

© COPYRIGHT 2012-23. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 256 bit secure checkout powered by stripe. |