|

If you are signed up to do legs 1, 4, 5 or 7, then you are likely to see the tropics at some point. Legs 1, 5, and 7, in particular, can be very warm for at least part of the time at sea. This brings with it several challenges, mainly revolving around choosing the correct deck clothing and apparel, managing fluid intake, personal hygiene and keeping cool below deck when off watch. Trying to sleep in 38-45º C, especially when it's humid and you are salt-encrusted & sweaty, is almost impossible until you are very very tired. Good, lightweight, wicking base layers with long sleeves (for UV protection) are critical. Don't use cotton. It gets wet, retains moisture once saltwater is on it and will get smellier, faster! A lightweight merino wool is good for comfort, performance and odour management. Icebreaker is a well-known Kiwi brand, although it is pricey.

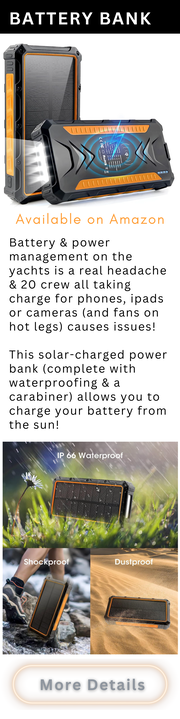

Many crew will purchase sunscreen for the crew but make sure you have a plan to protect yourself against exposure to the brutal tropical sun. This will also mean a lightweight, ventilated wide brimmed sunhat with a chin strap (unless you want to lose it on day 1). Bare feet on the deck of a Clipper 70 is a no-no. There are too many hard things to break a toe on. Believe me, you only kick a stanchion post once with bare feet to learn this lesson. Therefore, some robust, grippy well vented shoes are required. They should also be of a material that allows for them to get wet and not get smelly. Keen Newports (open sandals with toe protection) are very popular amongst crew for this reason. Below deck, many crew swear by Crocs. This fashion crime is between you and your own personal God! Finally, if you plan to send emails from your ipad or phone and run a fan, etc then you will need the option to run the fan and charge your gadgets. Clipper 70s have various charging points, but it is easy to overload the batteries and the circuits, especially as the boat needs to run satcoms, navigation equipment, water maker and things like rice boilers. When I was skipper, I set up a charging schedule which allowed the on-watch to charge phones and personal battery banks whilst they were on deck. This seemed to work quite well, but it was something else to remember on watch change. Forget to charge your battery and you may end up having no fan for your next sizzling off watch. For this reason, I'd suggest you consider a battery bank for charging your kit. 30,000 mA as a minimum, should suit. You will also need a means of fixing this to your bunk when in use. I used some heavy duty velcro. I'm particularly impressed with some new battery banks which have a solar charging option. They are claimed to be robust, dust & splash proof and are able to be secured somewhere appropriate on deck by way of a carabiner. This gives you the option to always be able to charge your battery.

Last of all, in the tropics, the opportunity to shower in heavy rain showers presents itself from time to time. Keeping the crew and the boat as clean as possible is important, especially in the tropics, unless you enjoy tummy bugs and pink eye.

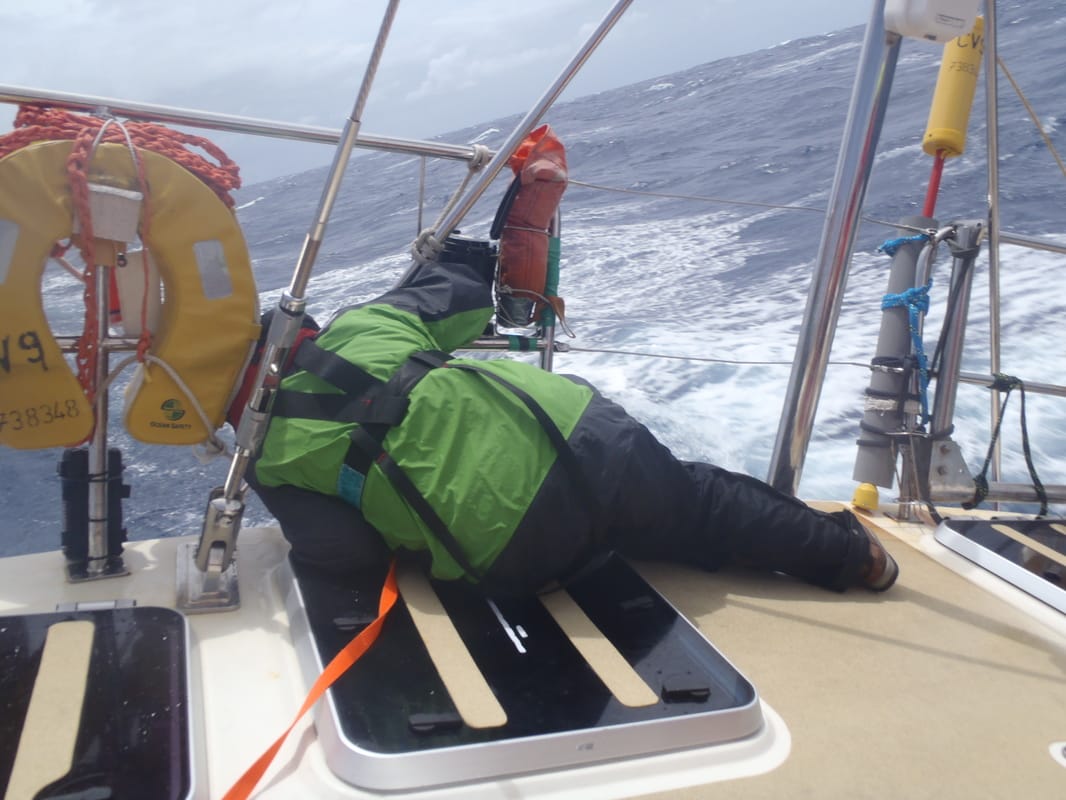

A small bottle of soap, easily to hand, will allow you to take advantage and soap up and rinse off (assuming you are not sailing the yacht, of course. Some crew are less modest than others, but a good place to wash is behind a helm station, offering some privacy. Even without a rain shower, a clean bucket and some sea water can be refreshing in hot weather. However, you really need to rinse in fresh water after, because salt water showers just make you sticky and salty. Some boats carry one or two fresh water solar showers which work really well when hung off the A frame on the stern. Finally, remember to stay clipped on at all times where SOPs require and keep your lifejacket on.

Comments

This is a video recording of our first monthly webinar broadcast on our Fierce Turtle Facebook page. We hold a webinar on the last Saturday of each month.

This video goes through kit organisation. In this short video I discuss what you should be thinking about packing for a cold ocean leg. In this context, I consider Cold Ocean Legs to be Legs 2, 3 , 4, 6 and Leg 8. Fierce Turtle (Packing for Training) : http://bit.ly/PackingListfortraining Check Out our Classified Pages for pre-used kit:

https://www.fierceturtle.co.uk/pre-used-kit Le Chameau Boots: http://bit.ly/sailingboots Ocean Sleeping Bag Hire: http://bit.ly/oceansleepingbag Sailing in the Southern Ocean in Summer is a tough old gig, even for the pros on The Volvo Ocean Race. It seems no coincidence that so many use the Le Chameau Neptune boot for the really tough, cold race legs.

Click here for our review of the Le Chameau Neptune. Clipper Crew can claim 15% OFF the Le Chameau Neptune if purchased in February 2018. The DISCOUNT CODE is WARMFEET. Just enter the code at checkout. Sail safe. If you look at the geography and the prevailing trade winds, it's pretty obvious that to sail around the World today (if you start in Northern Europe) then you have to sail South across the Atlantic and then either go East or West. Going East is far more sensible.

With this reality in place, it becomes likely that Brazil and South Africa are going to be two of the first ports of call. Going East, Western Australia makes sense and then you have to get to China for the Qingdao stopover (which is not to be missed for spectacle). Whilst in Oz though, it seems appealing to compete in the Sydney Hobart Race so continuing East, either around New Zealand or Tasmania, Sydney has been a regular stop for the last few races. Before that New Zealand and then Australia's Gold Coast were stopover ports. Leg 4 is, therefore, usually Western Australia to East Coast Australia, perhaps including the Rolex Sydney Hobart after Christmas and then a short hop back up the East Coast. The leg needs to advance the race to China. Going East around Australia makes some sense as there's a large continent on our doorstep. Because it's Christmas Sydney Hobart is a possibility. Then you need to go North to get around Australia and back towards China. This means lots of races The advantages to Leg 4 are, in my opinion, as follows; PROS

CONS

All in all, I'd say Leg 4 is a good leg. It has several races, it's set in a great part of the World and there are iconic events and locations all around you and a mix of conditions. What's not to like? Leg 3 is a biggy ! The Southern Ocean must surely be on every offshore sailor's bucket list. The 'Roaring Forties' below 40 degrees South are renowned for massive low pressure systems and monster waves. Crossing from The Cape of Good Hope to Cape Leeuwin (or thereabouts) means that you have undertaken a big challenge. It gets cold, wild and wonderful. In previous years the race has started in Cape Town and finished in Western Australia (usually Albany or Geraldton).

Pros;

Cons;

(aKnown as one of the 'glory legs' because you get to start the race with all its associated excitement, leg 1 is a long leg (about 5,000 miles). Sometimes split into two races, the leg takes you across the North Atlantic, the Doldrums and equator and delivers you to the southern hemisphere on the South American continent. It is generally warm (sometimes very hot) and the weather is generally less demanding than most of the other legs - although you will see what you think is big weather along the way.. That's until you've finished leg 3!

Pros;

Cons;

That's my view but if you have a different take on things, please feel free to comment below. If this blog is helpful please consider liking and sharing on Facebook. To subscribe and hear more about the other legs and the race in general, plus crew discounts and flash sales, subscribe. Regular, preventative maintenance of your boat and its systems is critical when undertaking an ocean passage; even more so when you're pushing the boat in race trim. A significant part of your maintenance programme will include your sail wardrobe and standing and running rigging. To check the rig, blocks and halyards, you're going to need to do a mast ascent and this will mean undertaking a risk assessment. Yes, yes, 'Health and safety', but believe me, the first time you leave the rig in an unplanned swing, you'll be a believer! Climbing a rig when underway is different to when sitting alongside a dock.

If you plan on being up there a while, a 70 cm long strop with a carabiner clip on both ends can be useful for attaching yourself more securely to the mast whilst working aloft. Once the climber is ready, check the lines for the climb as follows;

Before you start the ascent, you are going to need something to stop you swinging off the mast and acting like a conker, halfway up. There are a lot of hard, sharp bits of metal up there and you get quite a speed up if you do start swinging. Trust me, I know. I'd recommend using your safety line. Clip it to your lifejacket hard point, then put it around a halyard that goes to the top of the mast (on the same side as the ascent) and clip it back to your jacket. This way, you are not 'connected' to the third halyard but, if you lose connection with the mast your swing will be limited to 2 or 3 metres. It'll still hurt, but you'll be under some control. If you don't have a spare third halyard then rig a downhaul line, attaching it to your harness strong point and running it down to deck, preferably through a block near the mast foot at deck level and back to a winch. This too, will help arrest a swing. On a very large vessel, a downhaul must be used, otherwise, there might come a time where the weight of the halyard in the mast overcomes the weight of the climber and at that point up you go! Not pretty. On the ascent, if you are fit and strong enough to climb, make sure your crew mates know so that they can take up slack as you go. If you're going to be winched, try and stay on the high side and ascend spiderman like, making sure to keep hold of the mast and rigging as you go. If the boat is heeled over, stay on the windward side of the mast and that way you have gravity working on your side. Watch you don't get fingers and heels stuck in the nooks and crannies of the rigging. As you go up, someone needs to be running the deck, making sure winches are being handled properly. Someone should also be 'eyes on' the climber at all times, relaying signals as they ascend. Once there, the halyards should be secured and I'd recommend a clove hitch on top of the winch turns at the end, so as to prevent a line coming off a winch or someone accidentally removing the line. On this point, never leave your winch when there is a crew member on the end of the line! Close the clutches on the halyards if you have them. On descent, first, open the clutches, then remove the clove hitches. Take the primary winch down to the number of turns that will allow you to ease the climber freely, but under control. This will vary dependent on the halyard and winch size but three turns is probably good. The secondary winch needs to be eased faster than the primary (otherwise it'll be a jerky and uncomfortable descent for the climber). You might consider removing turns to 2 turns and let the line run freely as the primary winch controls descent speed. Don't let the halyards run through your hands. Ease them in long, smooth actions, hand to hand - their crotch area will appreciate it. As the climber descends, the person in charge keeps watching the climber at all times and communicating with the deck crew. Once back at deck, make sure all halyards are secured properly to the pin rail, making sure that each halyard run is correct and not tangled around the forestay or rig. Always look up when handling halyards to prevent this eventuality. Despite all of this, it can still go wrong. Just make sure you remain attached to the third halyard or downhaul and a painful swing is the worst you can expect.

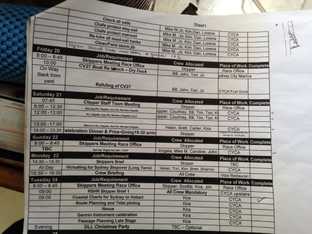

The boat must come first. That means putting together a full list of things to do and allocating crew to each task. You may have a long list of things to see and do, but there is a real possibility that a lot of them will have to be cancelled if the boat needs work. I say this now because, in my experience of two races, this becomes a real gripe amongst some crew. The fact is, even with the excellent support offered by the small team of shore crew, you will be busy during the stopover and you will be required to give time to the boat in one way or another. Part of the fun of circumnavigating is (or at least it was for me) being part of the circus that travels around the World every other year. Some ports are bigger than others and each one has its own charms. I will promise you one thing. After 3 or 4 weeks racing across an ocean, making landfall is a very pleasant experience! But when you get to the finish it's not all parties and story-swapping. There is work to be done - and sometimes lots of it. Also, if you happen to have had a bad race and finished late, you have less time in which to do this work.

This will include PR visits, radio and sometimes TV interviews, skipper meetings, corporate sailing days and the like. During my time as skipper I could never find enough time in the stopover - it was manic. On top of maintenance there are the corporate sails. These are days where the sponsors get to entertain clients on day sails. As part of your crew contract, you may well be required to participate in these days. I always used to enjoy these days, but they are full on and generally you have to write off at least half a day for this - assuming you swap out at lunchtime. Of course, as long as you get in on schedule there is no reason why you can't have 3 or maybe 4 days to yourself. The better you do in the race, the more time you are likely to have! So there's a real incentive to be first boat in.

Keeping warm at sea is just a matter of preparation and attention to detail. Of course, on some of the warmer legs, such as leg 1, leg 7 and much of leg 5, keeping warm on board is not a problem. In fact, dealing with 40+ degree temperatures and high levels of humidity below deck is the biggest challenge. If you want to read more on these warmer legs and how to keep cool, click here. In my experience, staying warm requires that you look after yourself by eating well, staying active and staying as dry as possible and as well insulated as possible. Staying active on the race is rarely a big problem but there is an art to choosing the correct clothing for the conditions. On a very cold night at sea, when it's wet and rough, with water over the deck (and the crew), staying dry and warm without overheating when busy changing sails, can be tricky. The start of a watch might have you thinking you are under-dressed, and feeling the bitter cold and yet 30 minutes later you might be sweating profusely having just dragged the yankee 1 down the deck, battling against sea state and gale force winds. Understanding the best way to layer is therefore important. For a cold ocean, you should be dressed as follows;

Those of you that have read 'Tales of the Riverbank', might believe that there's "nothing but nothing so absolutely wonderful as messing about in boats", but I'm pretty sure Badger and Ratty hadn't been on the weather rail all night, downwind of a projectile-vomiting Toad. 'Mal de mer' as the French would say, is basically motion sickness; the disconnect between what your eyes are seeing and what your balance receptors are telling your brain. It causes the body to react and it makes you feel nauseous - and sometimes vomit; sometimes spectacularly. In itself this is nothing but unpleasant, although in severe and prolonged cases it can cause dehydration and therefore result in further complications. It is therefore imperative that you keep an eye on a sufferer and encourage them (without nagging) to keep sipping water even if they are feeling very ill. Remember too, if you are taking medication, including the contraceptive pill, you are in danger of losing its beneficial effects after a bout of vomiting - even once home. If you suffer in cars or on flights, it is more likely that you will need to medicate when at sea in rough weather. Common sense would suggest that if you already know that you suffer, be prepared. The key is to medicate early (12 hours before you sail) if the remedies are to have a chance to work. They do say that there are only two types of people in this world; those that suffer from sea sickness and those that have yet to suffer. Most people are not normally sea sick, although many worry themselves unnecessarily about it. I'm one of the lucky ones. I did feel sea sick when I first started to sail 25 years ago but almost never was, except for one night in a F10 storm off the Moroccan Coast. Nowadays I don't even think about it - although I am very aware that we can all get it if a bit under the weather, so I am not saying it won't hit me again! Anyway, Lord Nelson was sick every time he went to sea and he was quite a decent sailor by all accounts. The good news is that sea sickness will pass. On the race a severe sufferer might be ill for 2 - 3 days. As the weather abates they recover. The more hydrated you stay the faster you get better. Most are only ill when it's pretty rough and even then, only for the first 24 - 36 hours of a trip. Unfortunately most early offshore phases in Training are 24 - 48 hours in duration, so if you are one of the unfortunates you might not see the other side of the sea sickness coin before you are back alongside. Don't worry - trust me - it will stop, eventually! In any event, like so many things at sea, look after yourself and look after your mate. Be considerate of those suffering - you might be next! And if you suffer, there are always drugs to help... The bad news is that there is no absolutely guaranteed preventative measure available in capsule form. You will need to try several if you suffer and work out what works for you. What makes you sick? A trigger with newbies is extended periods of time at the chart table - or in the galley, so try and avoid that if you start feeling ill and if you do feel poorly when cooking, take a few minutes to get some fresh air and check out the horizon - this really does help a lot. The smell of diesel or a flushed heads (toilet) can set you off too. You can see why being below is a factor for some. If you allow yourself to get too cold or too warm it can strike the more susceptible. It also prays on the hungover and those feeling 'under the weather'. Apparently, women having their period are more likely to suffer, although I'm afraid I'm no expert in that department and will steer clear of advice there. The classic for Clipper Racers in Training is after dinner on their first night at sea on L2. Eating too many stodgy carbs, going to bed on a full stomach and not getting horizontal fast enough when coming from watch (or changing below to get on watch) can bring it on in the most susceptible. The trick is to get to bed fast when going off watch and get to deck fast (dressed and kitted of course) when coming on watch. Fresh air and watching the horizon helps. Don't get too hot or too cold and sip water and nibble food regularly and you'll be fine. What are the Symptoms? Having sailed for 25 years or more, my general experience of the sea sick is that sufferers normally go quiet for a while first, then pale and sometimes they become cold and clammy. A friend of mine once went an unbelievable green and then deep deep purple. He looked rather like he'd been in a ring with Mike Tyson in a bad mood. It was a sight to behold and, in an uncharitable way, even quite amusing - for me at least. Needless to say, he was a very very old friend. I'm much nicer with training crew..ahem. Sufferers become lethargic and sometimes unsteady on their feet. They can also feel bloated and queasy. Sounds fun so far, right? Thankfully sea sickness isn't life threatening although they do say that the stages of sea sickness start with the sufferer fearing he's so ill he's actually going to die and then, after several hours, comes the awful realisation that in fact, he might not. Don't confuse sea sickness with hypothermia, a much more serious condition and, of course, being sick at sea might be a symptom of something else, so treat a sufferer like any other casualty once they become overcome by the symptoms and unable to function properly under their own steam. Many will never feel anything but just a bit queasy. However, especially if it is rough or you are spending extended times below decks, perhaps doing chart work or cooking, you might become nauseous and vomit. If you start, it's likely that you will soon feel unsteady on your feet and lose strength quite quickly once you are fully gripped by it, especially if you are not eating and drinking. But you can come back from it and some are much better after a quick 'tactical chunder'. It's up to you. What can I do if I get it? Most only ever feel 'a bit nauseous' but if it is rough you might actually have need to call over the side for 'Uncle Ralph' once or twice. Again, this is very personal to the sufferer, but most feel better right after. Some 'puke and play', carrying on as normal, some collapse in a heap of misery. Whilst there is some element of strength of character at play here (and adrenaline plays its part too), I really believe that some people just suffer more. It's not always something you can just power through. I have seen a World Class pro 'Cage Fighter' that knows about physical discomfort and managing it just crumble because of sea sickness. He later admitted he'd thought he could just power through, and he did try, but eventually it wore him down. He was the first to admit he had to find a way to manage it - and he did. Try and be brave if you are unfortunate enough to suffer. But if you try your best and have to stop, that's fine. After all, we want you on deck learning, not in your bunk being sick, so try and manage your body early and look after yourself. To anyone that sails, a crew member with sea sickness is no big deal. Throwing up in front of strangers isn't most people's idea of a fun day out but please don't be embarrassed. We've seen it all before. Take it from a man that has been puked on by many. Of course, I'd rather you didn't add to the tally, so please try and control your trajectory. Don't be embarrassed but do try and be considerate of others. If you get sick bad it can be very debilitating. That does not mean you can abdicate all responsibility for hygiene and social decorum, no matter how ill you might feel, try to plan where you puke! I don't enjoy being puked on any more than the next man. If on deck - clip on (of course) and try not to vomit into the wind - it is never a good idea and you'll only try it once. Helming is a good way to get rid of sea sickness. It gives you something to think about and it connects you with the motion of the boat. If all else fails, ask to go below and get horizontal in your bunk. Get warm and comfy and you should start to feel better. Take a bottle of water and some paper towel and a bucket just in case! If below and using a bucket, make sure it is passed to deck to be disposed of to avoid an unpleasant aroma gathering below. Top tip: Best warn the deck what's in the bucket! Most skippers like sufferers to be near the wheel somewhere so they can keep an eye on them - or lying down flat, securely in their bunk, with a bucket, a bottle of water and a warm sleeping bag. Hopefully some kind person will come and check on you every now and again. Try and stay hydrated and warm and don't be tempted to stay on deck on your off watch! You must go below or you'll become cold and dehydrated. Then your problems really start! There are a variety of pills and patches and wristbands available to the susceptible. Patches are quite good but very strong and all have side effects. Check restrictions on use. Ginger and flat cola are considered to be good for the symptoms. Some people use sea bands and some use tablets which you can get from any pharmacy. Whatever pills you take, take them at least 12 hours before you start sailing. If you start taking them late they'll have no time to work. Obviously, if you start vomitting, the tablets will stop working. That's when patches seem a good idea. Double vision, dry mouth and drowsiness are all symptoms of the remedies, so read the box carfeully. Remember, most people are not sea sick, especially in normal conditions. The most reliable way to avoid sea sickness is to stand under an oak tree. However, next best you can try wrist pressure bands, motion sickness tablets or patches. Ginger is said to help and flat coke too. Patches are good because you can't throw them up - worth considering. If you take pills, take them at least 12 hours before you sail, so the night you arrive on the boat before on a training course. If you wait until you feel ill, it's almost certainly too late. The patches are sold under various brands but I think Dramamine is the main brand. It is strong and does have side effects. As with ALL medication, read the labels before taking and if unsure, consult your doctor. |

Mark Burkes is a former Clipper Race Skipper, a round the world crew member, Clipper Training Skipper & jobbing RYA Yachtmaster Instructor. He has over 250,000 miles logged.

Mark also writes professionally both online and offline and has written for Yachting World. ADVICE BY TOPIC

All

Fierce Turtle is not linked to nor is it in any way accredited by the splendid folk at Clipper Ventures. All opinion is my own.

Archives

July 2023

This blog is entirely free. However, if you'd like to make a small contribution towards web hosting costs it'd be very much appreciated.

|

fierceturtle.co.uk |

PRIVACY & GDPR POLICIES

© COPYRIGHT 2012-23. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 256 bit secure checkout powered by stripe. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed